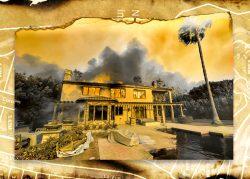

In November 2018 the Woolsey Fire ignited on a research property in the Santa Susana Mountains, near the border between Los Angeles and Ventura Counties. Pushed south by the Santa Ana winds, it went on to burn nearly 100,000 acres, kill three people and cause more than $6 billion in property damage. Much of the harm was concentrated in Malibu, where the entire city was put under an evacuation order and hundreds of houses — even close to the Pacific — were destroyed.

Since then the enclave’s housing market, already among the nation’s most expensive, has soared. Recent top-end sales have included Marc Andreessen’s California record $177 million purchase and two different mansion purchases, at $100 million and $87 million, by Jan Koum; in April Michael Eisner listed his five-acre, 25,000-square-foot compound for $225 million.

Throughout the Golden State devastating wildfires are nothing new. But they are getting worse by various measures––and over the past decade the state’s housing market has essentially shrugged: According to a new climate change-focused report published by Home Bay, part of the real estate company Clever, since 2012 many California metro areas have notched among the country’s highest median home price increases even as California suffered more weather and environmental disasters than any other state.

“The data and the lived experience are very clear that climate change is becoming more and more of an issue,” said Danetha Doe, a representative for Clever.

But those trends are “not impacting the home prices or the demand,” Doe said.

Home Bay compiled its report by analyzing disaster data from FEMA, the National Interagency Fire Center and the National Centers for Environmental Information, as well as housing data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, which tracks median sale prices, and the Zillow Home Value Index.

The FEMA data counted the number of “weather and environmental disasters” declared by the agency in each state between 2012 and 2022: California, with 146, had the most, followed by Washington State (85), Oregon (58), Oklahoma (42) and Montana (37). The majority of California’s declared disasters were wildfires, although there were earthquakes or other disasters in the tally.

FEMA also expects California to continue suffering. To assess future risk, the agency assigns each state an Expected Annual Loss score from 0 to 100: California was the only state to score 100, reflecting a vulnerability that continues to be amplified by climate change.

“We’re seeing it year after year for the last few years,” one fire chief recently told the Los Angeles Times, as experts warned of yet another dire fire season. “We’re getting hotter, drier, faster.”

The state’s housing markets, like Malibu, have been characterized by consistently strong demand and limited supply, leading to a long-term market surge in recent years. Per Home Bay’s report, since 2012 median home prices in markets ranging from San Diego to Sacramento are up over 140 percent: In L.A., Home Bay found an increase of 147 percent; in San Jose it was 190 percent.

Riverside’s median was up 183 percent. Over the past couple years, as prices in the Bay Area and Greater L.A. drove many residents out, the traditionally more affordable Inland Empire emerged as among the nation’s hottest housing markets: In 2020, the two-county region tied with Phoenix for the region with the biggest influx of new residents, and early last year it also saw the country’s highest spike in rent prices.

Yet Riverside County also has more properties at risk of wildfire damage than any other county in California, according to a report published in May by the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that assesses flood and wildfire risk data. Heavily populated Los Angeles County ranked second.

More expensive or unavailable fire insurance coverage, along with local legislation, could end up eventually cooling the housing market in fire-prone areas, Doe predicted. But don’t expect a wildfire-driven California exodus.

“There’s dangers everywhere,” the star broker Chris Cortazzo, who lost his own home in the Woolsey Fire, told TRD early last year, articulating a viewpoint shared by many. “You can be in Texas and freeze to death. Or you can be in Oklahoma and get wiped out by a tornado. The reward far exceeds the risk.”

Read more